The painting above appeared in a post, My Father – A Life Worth Living, from Vitaliy Katsenelson’s blog “The Intellectual Investor.” In describing his father, Vitaliy writes that it wasn’t until he studied Stoicism that he realized that his father lived by Stoic principles. It was an exemplary life, and the post, including a home video documentary about Naum Katsenelson, is well worth your time. (That’s my opinion…it’s your time, so you decide.)

Running across this blog post about Vitaliy’s father is only one instance of the times I have stumbled into references to Stoicism in the past year. How did this ancient Greek/Roman philosophy first enter my awareness? I was having lunch with my friend Eileen, telling her about another friend who is often utterly stupefied when her life changes — advancing one more year in age, loved ones dying, her adult children choosing to live differently from her. All of these changes, if considered rationally, are simply part of being human. Her reactions seem to indicate that she did not have a clue that difficulties like this would happen as a matter of course. I told Eileen that I must be either a realist or a fatalist, because I don’t understand being startled by events that are normal realities of existence — sad, dismayed, heartbroken, yes, but surprised? Her response was, “It sounds like you’re a Stoic.” So I started reading up on it. I found that yes, I have a few Stoic tendencies, but I’m far from being able to define myself as a Stoic. I continue to explore and consider…

Apparently, Stoicism is in the air lately. I was visiting my son Sam in Oakland in July, spouting off about all I was learning about the philosophy by reading and listening to podcasts. He said that Stoicism is all over social media with comments from both proponents and detractors. Apparently, it’s a bandwagon. I’m glad I didn’t know that when I started learning about it, because I have always made a point of not jumping on bandwagons. (I may have missed out on some valuable experiences, but I can live with that.)

I had second thoughts about whether Stoicism is for me when I saw the video “What Is Stoicism” by Ryan Holiday. Through his books and his TEDx videos, Holiday has introduced many people to Stoicism. His website The Daily Stoic (where you can see the video) has an enormous amount of information about the history of Stoicism and the originators and teachers of it in ancient Greece and Rome. He has written numerous books on the subject, which have attracted a huge following. However…

In the video mentioned above, the handsome, charismatic (if you like that sort of thing) Holiday talks about the main tenets of the philosophy, and while he does so, you watch a constant stream of background videos. In them, Holiday himself is shown doing hard, athletic workouts, speaking to groups of “important” people (NFL players, Wall Street figures, etc.), and constantly journaling. I am bothered by both his representation of himself as the very model of a modern major Stoic, and even more by his marketing of courses on Stoicism, medallions with Latin phrases that Stoics use, and pendants with the same phrases at $245 each. If he is really trying to make Stoicism accessible, he’s missing the mark, at least for me. (The workouts alone make me feel unworthy to even try Stoicism. No way could I pass the physical.)

As Marcus Aurelius once said:

from a post on Reddit by one of Holiday’s detractors

“Waste no more time arguing over what a good man should be, sell merchandise t-shirts and coins online for $40”

Put off by Holiday’s approach, I have read and listened to podcasts by two other Modern Stoics, Massimo Pigliucci and Donald J. Robertson, and found them far more to my liking. Pigliucci started his career as a biologist, Robertson as a cognitive-behavioral therapist. The podcasts are called, respectively, “Philosophy as a Way of Life” and “Stoicism: Philosophy as a Way of Life Podcast.” Both promote the Stoic way of life as something to strive for rather than something to perfect. Neither considers himself a Stoic sage. This makes being a Stoic seem more approachable, more practical, and worth pursuing.

I’ve also dipped into the source material, which includes the writings of Epictetus, Seneca and Marcus Aurelius, but I find modern books on Stoicism that present the philosophy, and acknowledge the advances made in understanding cognitive science since ancient Greek and Roman times, to be more immediately understandable. My favorite so far is The Practicing Stoic by Ward Farnsworth. The author presents one facet of Stoic philosophy in each chapter (e.g., Judgment, Externals, Perspective, Death) with citations from many sources: the three canonical Stoic philosophers, Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius and Seneca, as well as later writers whose views channeled and expanded on Stoic thought. These include Montaigne, Samuel Johnson, Adam Smith and Schopenhauer.

I hesitate to give a short description of the Stoic philosophy because 1) I’m not an expert, and 2) there’s more to it than a quick explanation can cover. But, here I go.

the essence of stoicism

It’s important to understand that “stoic” as used in modern language does not represent accurately the philosophy of Stoicism that was described in ancient times. “Ancient Stoicism does not involve the simple suppression or closeting of emotions. The Stoic is not without emotions, but without painful or unhelpful emotions such as anger, envy, and greed.” This quote is from a short article from Psychology Today that gives a good, short explanation comparing stoicism with Stoicism.

One of the first concepts that I learned about Stoicism was what is called “the dichotomy of control.” Essentially, it’s the Serenity Prayer. Distinguish between what is up to you and what isn’t. When something is not up to you, let go of trying to control it, and strive to find a way to respond with equanimity. When it is up to you, act.

- Not in your control: Loss of a job, health outcomes, death of loved ones.

- In your control: Your response to any of the above.

Memento mori – always keeping in mind the fact that death will come to you and all you love, not so you live in fear, but to acknowledge that universal truth, keep life in perspective, and appreciate the value of the present.

Amor fati is a Latin phrase that may be translated as “love of one’s fate”. It is used to describe an attitude in which one sees everything that happens in one’s life, including suffering and loss, as good or, at the very least, to be expected.

The view from above – This change in perspective is recommended by the Stoics as an antidote to living. This is illustrated in View from above: a Stoic practice for daily perspective. I love a book called Zoom by Istvan Banyai. Ostensibly, it’s for kids, but I have given many copies to adults as well. There are no words, just drawings. Each page zooms out from the drawing before it. The effect is fascinating and, for me at least, calming. I regularly buy several copies, often used, to have on hand. As Tobias Weaver says, “When we change the way we look at things, the things we look at change.”

The four virtues named by ancient (and modern) Stoics are wisdom, courage, justice and moderation/self-control. At this point, I strive toward the first, usually have a modicum of the second, have a strong sense of the third, and am far from exhibiting the last.

I wrote the above self-assessment paragraph a few days ago. I’ve been mulling it over, and my claim to have “a modicum of courage” is overly generous, since moderation/self-control is at least partly dependent on courage. It takes courage to stick with an exercise routine, to eat moderately and healthily, and to recognize irrationality in my behavior so as to diminish the frequency of the outbursts you’ll read about below. So, to be more accurate, I have the courage to confront bullies, but need to develop the courage to be more even-keeled in daily life.

I believe that my interest in Stoicism can be explained by its contrast with the “philosophy of life” that I learned by osmosis when I was young.

the world according to dorothy

My mother Dorothy was the dominant figure in my childhood. Her habit of mind was anything but a Stoic one. In the world she grew up in, the general rule was to carry on as your parents had done. Introspection was likely considered a luxury since “Idle hands were the devil’s workshop.” Psychotherapy was unheard of. The modern definition of lower-case stoicism might have applied to the messages she received: “Quit your bellyaching, there’s work to be done” typified the ethos. There was a lot of work, so I get that, I guess.

As I wrote in a previous post, Dorothy went through a major trauma in 1943 at age 21, losing her husband of two months to an airplane crash while he was in pilot training. She had a miscarriage at his funeral. Bob Pinkerton, the man she married, had offered her the hope of a new life. She would no longer be the eldest daughter in a big family, shouldering the burden of housework and child care while her brothers were given more freedom. She would have wings.

But it was not to be. Dorothy was raised a Presbyterian in a small town where most people were also churchgoers. This is reflected in the kinds of sympathy notes she received after Bob’s death: “I know you are taking strength from the knowledge that for Bob, there was no death, and that even now he lives with his Lord and Savior, whom he loved and served so faithfully throughout the years. He would not have you mourn — and sorrow as though without hope — but rather rejoice in his victory: Eternal life through Jesus Christ, his Lord.” Another note reminds her of the Tennyson quote, “Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all,” followed by the advice, “Consider the Book of Job.”

So, the Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away. The vicissitudes of life are handed out by God — randomly, it appears, though it would have been hard not to take your husband’s death personally when you’ve been told that God loves you.

The one facet of Stoicism that Dorothy seemed to embrace was memento mori. Not surprisingly, I guess, death was always on her mind. When one of us was late coming home, her assumption was that we were injured or dead, once colorfully expressed as “splattered all over the highway.” This, however, is not the memento mori the ancient Stoics had in mind. They did not mean that life is better when you live in constant anxiety, just waiting for something awful to happen. Sometimes I wonder whether she believed that worrying was prophylactic: “If I worry enough, all will be well.” It kind of seemed that way. Maybe at the moment when Bob’s plane went down, she was calm and peaceful, but then reasoned later that worrying might have prevented the crash?

In the post called “my mother’s pain,” which I linked to above, I wrote, “…my relationship with my mother over the years, which was often loving, cordial and full of humor, was punctuated throughout my childhood and adulthood with unpredictable encounters with her irrational, out-of-proportion anger and hypersensitivity to what she considered personal slights.”

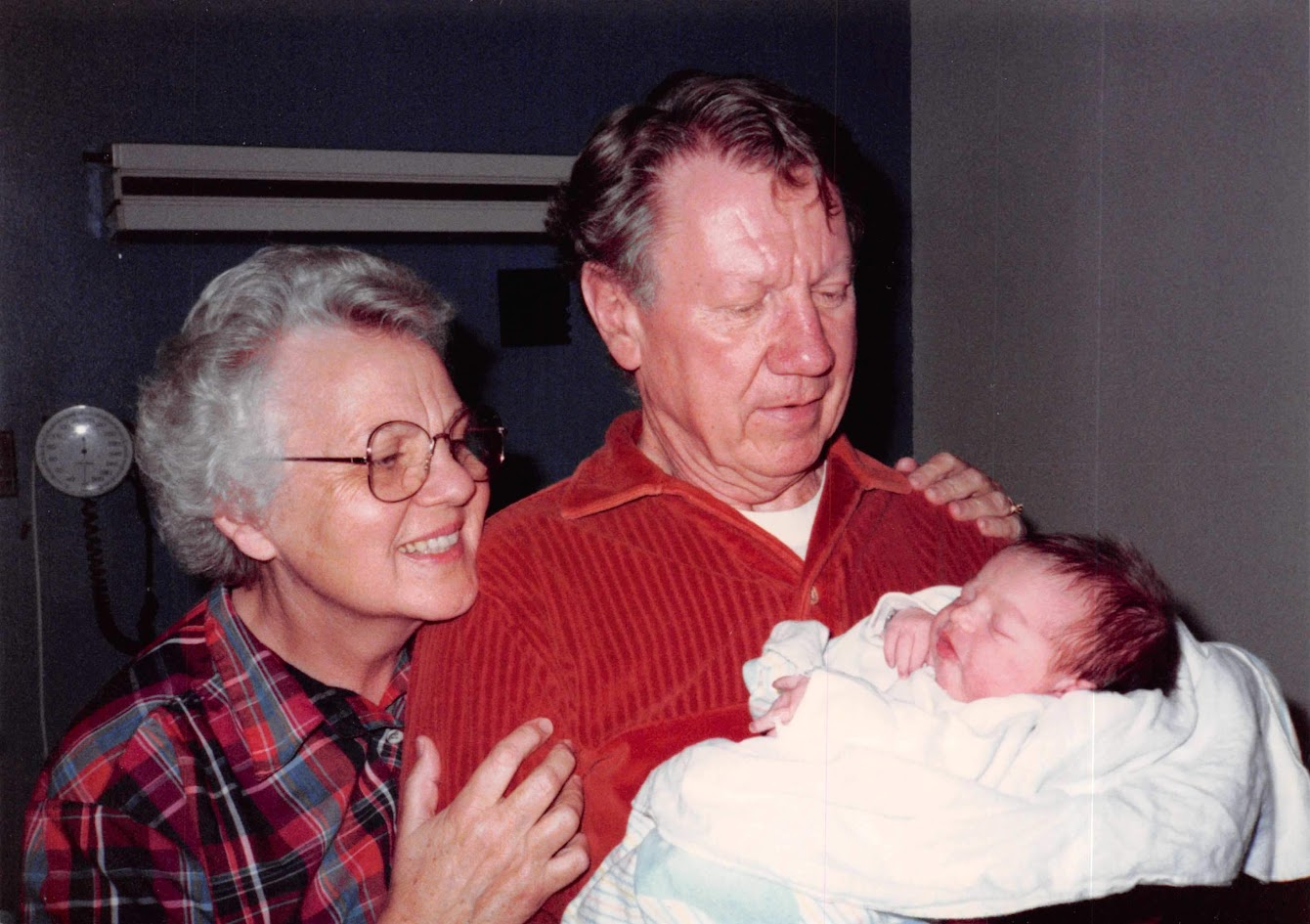

My siblings and I were targets of these episodes rather regularly. We all experienced the whiplash of her anger personally, but also witnessed her obvious frustration with my father, Ralph, who was frequently subjected to her lashing out for his supposed inadequacies. He, after all, was not Bob. Because of who he was and prior experiences he brought to the marriage, he was abjectly contrite when Dorothy accused him of insensitivity to her needs. He simply absorbed the shame she threw his way. He was confounded about how to please her. Observing Mom’s dissatisfaction with him, I grew up seeing things her way, thinking that Ralph was a doofus. (I must admit that he was kind of quirky, but who knows how different he would have been without her constant reproaches). I’m sad that I bought into Dorothy’s negative view of him. He tried so hard.

One funny/sad example of their interplay: Dorothy loved to tell about a road trip they took. After some time, she began to feel hungry, but rather than saying so, she asked, “Ralph, are you hungry?” His answer was “I’m not suffering.” According to Dorothy, this exchange happened several times. Each time, she became more and more exasperated. I’m not sure exactly how this ended, but probably with a minor explosion in which Ralph was accused of being insensitive to her needs, which, of course, had never directly been expressed. She told this story to make clear to others just how tone-deaf Ralph was. Oy.

Ralph died in November of 2012, and Dorothy in January 2013. Fortunately, in the last few years of their lives, they actually became friends, spending more relaxed time with me and my siblings, their grandchildren, and each other. The tension was mostly gone, allowing for real enjoyment of their time together. I was able to spend individual time with my dad before he became very ill, and we both enjoyed talking and laughing together. I also spent three weeks with my mother as she was dying. She was calm and peaceful, but expressed regret about how angry and punitive she had been. I assured her that, on balance, she gave us more love than anger, and that we all survived.

The last 10 weeks before Ralph died, the two of them were isolated from each other due to a medical quarantine as an intestinal illness raged through their retirement home. Dad was in the last stages of congestive heart failure, so was living in nursing care quarters while Mom had a room in assisted living. The quarantine was lifted the day before Dad died, and Mom went to visit with him. According to Mom, when she came into his room, “his face was alight.” They spent a couple of hours sharing memories of their lives together — the grandkids, their mountain home and their travels. Dad died the following morning. The memory of that precious time with him stayed with Mom until her death two months later.

I replicate dorothy

Richard would attest that in the first few years of our relationship, he had the dubious privilege of being subjected to “Dorothy behavior” from me quite often. I still act that way from time to time. I’m sure that my kids, despite my attempts to employ more humane and effective strategies in parenting, no doubt felt some of that anger and shaming come through to them. I can barely stand to remember the shaming I subjected a beloved student to when he absconded with my transistor radio (of all things) early in my teaching career. Impulsive overreaction to perceived slights is quietly waiting in the wings, ready to pounce, now almost exclusively (and much less lethally) with my long-suffering husband.

Richard has his issues, too, of course, and we went through 20+ years of counseling, which helped us understand these interactions. (We’re slow learners, I guess.) He learned not to accept blame, but to stand up to my irrational anger. His confronting me went some way toward altering my behavior, but I continue to natter at him on an almost daily basis. More often than not, we end up laughing about it. It’s so much part of who we are together that I can’t imagine letting the pattern extinguish itself through non-use. I think of it as everyday patter, but still occasionally take it too far and need to be reminded to back off.

I experienced no horrible, traumatic life events to explain my replication of my mother’s anger and hypersensitivity — unless you count the trauma induced by being one of the targets of her particular brand of “guidance.” I’ve overcome the worst of it, but it is still, alas, with me.

I believe that it may be largely because of the irrational, outsized irritability and family drama that I grew up with that I was attracted to Stoic philosophy. It would be a relief to leave irrational, emotional thinking behind.

the wisdom of gary rhodes

I have several friends and acquaintances who, like Vitaliy’s father, may not consciously be Stoics, but seem to naturally live their lives according to Stoic principles. In a way, it’s not surprising that such people exist. After all, the ancient Stoics didn’t invent the philosophy from thin air. They observed which attributes of character in themselves and others led to more equanimity and resilience.

My cousin Janice, who I visited and wrote about in the Wichita post, was married for over 54 years to Gary Rhodes, who died of cancer in June, 2023. Janice and I spent hours talking about all kinds of things: our shared extended family, our offspring, and the deaths of Gary and Janice’s sister Patty. It turns out that Gary was, whether he knew it or not, an exemplar of Stoicism. He took things as they came, was a realist, and was not surprised or thrown off balance by unexpected (but universally inevitable) events.

An example: When a doctor, after seeing Gary’s MRI scan in 2005 when he was first diagnosed with cancer, gently told him that he had a mass in one kidney. Gary’s reaction was anything but typical. When he didn’t show a response, she asked whether he had heard her. His response was, “Why not me?” I was astounded when I heard about this. In my experience, the usual reaction in this situation is, “Why me?”

I have only had one brush with a potentially dire medical diagnosis in my late forties. I remember feeling knocked off-balance, confused, and frightened. I don’t remember a strong “Why me?” response, but I assure you that “Why not me?” was the last thing in my addled mind.

In a recent phone call with Janice, I asked about whether Gary had always been philosophical when dealing with the ups and downs of life. She reminded me that in the late ’60’s, early in their marriage, he spent a year in Viet Nam. He was in a position that kept him out of the fighting, but was close enough to it to see friends die and to be exposed to Agent Orange. He returned home with a fresh awareness that death is an unavoidable reality. He did not expect to live a long life due to the exposure to Agent Orange. In fact, Janice had to talk him into having children because he didn’t think he would live long enough to help raise them. That experience alone may have set the stage for having a mindset of rational acceptance of things beyond his control or, maybe, Gary was a natural-born Stoic.

Janice says that, although he never explicitly said so, he wanted to be sure that if he were to die first, she would be able to carry on without him. He encouraged her to pursue her own interests and hobbies as he did his, to get together with her friends and have an independent life alongside what Janice calls their “mighty fine” married life. That was a gift from Gary to her. No doubt she experienced enormous grief when he died, but she did not doubt that she could carry on.

As it turned out, they had two children and a long, happy life together. He and Janice were both elementary school teachers for many years and Gary eventually became a principal. He was a very big guy — six feet, six inches. I love imagining him in front of a classroom of young kids. I’m sure he was an unforgettable teacher.

Gary had the wisdom and perspective to know that, like all of humanity, he was not immune from the inevitable. When the cancer returned a couple of years ago, it was Gary that reminded Janice, their kids and grandkids that (holding up his index finger and thumb an inch or so apart), “life is only this long.” Shortly before I visited Janice in June this year, and one year after Gary’s death, Janice received an email from the hospice chaplain who had spent time with him in his last months:

Gary’s peace with his diagnosis and pending passing was very remarkable – I’ve seen a lot of people after their terminal diagnosis, and Gary stands out as the most peaceful, accepting, and curious person I’ve known. I used the word “curious” because he would say, “Look at my arms, how they are withering away. Isn’t this just so fascinating?” He didn’t say it with anger or frustration, but with a sense of watching his body in a matter-of-fact way, with curiosity and a love for learning, even learning about the death process!

so, is it in me to truly be a stoic?

It has taken me far too long to write this much — writing, deleting, rethinking, rinse and repeat. I’m not claiming to have been in deep thought about Stoicism throughout these months. I don’t take myself quite that seriously, but… I do aspire to be more rational, less easily thrown off balance by the state of the world, and less prone to irritation and self-recrimination.

I will never be a Stoic sage (since such a person does not exist, with the possible exception of Gary Rhodes), so what Stoic practices can I reasonably adopt?

It’s equanimity I’m after. To be continued…

in the meantime

Up to now, I have had an electronic keyboard in our Flagstaff home, but not a “real” piano. A few weeks ago, I had 15 minutes before meeting a friend, so I stopped by an estate sales and liquidation place where I’ve found a few other things for the house. I walked by a Yamaha piano, glancing at it as I walked past, then walked backwards a few steps to look at it again. I’m not an expert, but when I opened it up to see the strings and hammers, they looked to be in great shape. The soundboard was also intact, so I impulsively decided to buy it. Pianos are not hard to find these days, and I’m sure I could have waited and found one for less money, but $850 sounded reasonable. Just this afternoon, I had a technician out to look it over and tune it. My instincts were good. He told me it was made in the US about 10-15 years ago, and the little bit of wear on the hammers suggested that it had maybe been played 100-200 hours. It’s a keeper!

I heard this Rameau piece on a classical music station recently, and found it both moving and calming. It sounded like something that I would be able to learn, so I found the score and am halfway to getting it under my fingers. There are a couple of spots where, because my hands are not the size of Rachmaninoff’s (see video below), I have to leap a bit, but it’s coming along.

Now this kid, for his age, has amazing technique and hand span!

Oh the places you go with your mind Susan…. Thanks for the enlightenment.

LikeLike