I taught for 45 years, the first ten in public school districts, then in my own tutoring office. Since retirement, I continue to tutor a few kids, partly to continue using the skills I have, partly just to be with children. My life has been full of children. In high school and college, I did not date, but babysat. For six or seven summers between college years and teaching years, I worked in parks and recreation programs, first in Colorado Springs, then in Tempe, AZ. I have been seen by others as having a knack with kids, and I usually do, but certain students have the ability to render me at least temporarily “knack-less.” I’ve come to an impasse with one such student this summer as I attempt to help him prepare for 5th-grade math. I’m hoping that by telling the story of my history with Charles will give me some insight for our upcoming session, because at the moment, I’m stuck.

Charles started tutoring with me the summer after he completed second grade. He was attending BASIS, a charter school that prides itself on pushing kids to be at least one grade level ahead. Don’t get me started on schools like this. They may be appropriate for a small percentage of high-achieving, go-getter students, but I believe that some well-meaning parents choose them because they are impressed by their high ratings in “Best Schools in AZ” and the US News and World Report. Those ratings are based on data, starting with students’ test scores, and extending beyond that to which high-falutin’ colleges accept their graduates (another bête noire of mine), how much scholarship money they receive, their rate of graduation from college, and other factors. Those well-meaning parents often fail to consider whether such a school is a good fit for their child.

The BASIS brochure states: “We are committed to the philosophy that all students [emphasis is mine] can succeed when provided with an advanced curriculum and supportive, knowledgeable teachers to guide them through it,” but the reality is that the reason graduates do so well is that a majority of students who start at BASIS drop out. In my opinion, it would be far more honest to have rigorous entrance requirements and admit that they are selective, but charter schools are public, so they can’t do that. My experiences teaching special education left a bad taste in my mouth for public schools (or companies, or governments, come to think of it) that draw lines between the sheep and the goats, leaving the goats (my students) to languish.

Charles was as high-strung as any student I’ve ever worked with. He startled at the slightest noise, would not use the bathroom unless I stood outside the door, and at the first session, broke into uncontrollable sobbing because he was afraid his dad would not come back to pick him up when our time ended. It wasn’t until the end of summer that we had a breakdown-free session. I believe the only reason he was willing to keep coming was the points for prizes system that I offer for especially discouraged students. His behavior and affect was much more like a four- or five-year-old’s, as his inevitable choice of Beanie Babies for prizes indicated.

There was a sweetness about Charles, and he was imaginative and funny when relaxed, but the numbers of fears he confessed to led me to writing down a list of them at the second or third session. I recently recounted that incident in edging toward spry in the “out of the mouths of kids” section at the bottom. In that post, the story was a lead-in to a funny quip. This time, it’s a backdrop to where we are now.

Charles made some progress over the summer, and his emotional eruptions became less frequent. I tutored him through third-grade math at BASIS, where they moved the whole class on to the next objective whether the last one was mastered or not. Charles’s mom got no feedback from his math teacher, which was puzzling to me. The teacher didn’t seem to notice (or care) that he was still struggling with old material as the new came along. In our tutoring sessions, a recurring pattern was that when he showed up with new math material, the door to his brain would have already slammed shut and he would sob, ” I don’t get it!” but aside from these short episodes, he was generally more emotionally stable.

In the fall of his fourth-grade year, something happened in his home life that was traumatic for him. I don’t know the details, but his dad was suddenly no longer there, which was clearly throwing him off his already shaky sense of security. I did not bring it up in sessions and tried to keep him in a learning state of mind, but at the same time, the school math continued to be more challenging. His memory for what he had learned before was hazy, he was not fluent in his knowledge of multiplication facts, and multi-step processes called for more patience that he had. He came to tutoring with one goal: “I want to get my homework done.” He became upset when I spent any time in review or explanation. It didn’t matter to him if he didn’t understand well enough to do the work on his own. He often didn’t.

A month before the end of fourth grade, his mother pulled him out of BASIS and started him at the local public school. Although nervous about the change, Charles was relieved, and seemed to get along well in those last weeks. His mom and I worked out a schedule of six 90-minute sessions over this summer to review fourth-grade and preview fifth-grade skills. Since we were to be in Flagstaff most of the time, we would work on Zoom. This works well for older students, but it’s not ideal for Charles. I was determined, however, to make it work.

In preparation, I worked for several hours familiarizing myself with the objectives covered in the curriculum, and prepared a resource notebook for him to use over the summer and during his fifth-grade year. I included “anchor charts” (sort of like cheat sheets — illustrations of sample problems) for each objective. I was on a mission. As often happens when I prep for a student, I became overly ambitious and excited about the task ahead. I knew we would not come close to covering everything, but had high hopes that he would throw himself into learning under my masterful guidance. “Pride goeth…”

I have tutored a few students who join me in my high hopes, enjoying the challenge of learning new material. I somehow lost track of the fact that Charles was not likely to be one of them.

The first Zoom session went well. Charles, unprompted, said that he wanted to be ready for 5th grade. He agreed to do a minimal amount of homework between sessions so that he wouldn’t forget what we worked on, with a reward of a movie gift card if he finished it. (There was a year between Beanie Babies and movie gift cards when he worked without reward, but I anticipated a need to reinstitute them this summer.) Before the second session, Charlie completed the items I had assigned.

We happened to be in Phoenix that week, so I saw him in person. He had made errors in a few decimal subtraction problems he did at home, but when we reviewed them, he saw the simple error he had made and willingly did a few more to demonstrate what he had learned. We were off to a good start. Then, I gently broke it to him that the answers to all four of the 2-digit x 3-digit multiplication problems were incorrect, and he crumbled. I attempted to have him take a look at the first one he missed, but as I went through the steps, he was blubbering, “That’s how I DID it!” I just let him cry for a while, then suggested that he give it one more try, but there was no going back.

It devolved from there. He was, to all appearances, inconsolable. I have wondered for some time whether, for Charles, this is a knee-jerk response to anything less than glowing feedback. At other times, talking about another student bursting into tears, I might be reporting, “My heart went out to him,” but not this time. What I wanted to say was, “Oh, grow up!” Instead, I stayed quiet for a bit, then reminded him that he had often responded this way when we were first working together getting ready for third grade, but he had grown up a lot since then, and I felt sure he could learn this, too. No go. He not only denied having grown up, but said he wished he were a baby again, because “they have no stress.”

Thoughts going through my head: I’m putting in effort and he isn’t. I’m too old for this. I’ve lost my touch. I don’t want to do this anymore.

My friend Carolyn is a brilliant, now-retired therapist who specialized in children. When I talked to her several months ago about Charles, she said it sounds like he has “emotional dysregulation” issues. As the article in the link states: “When a person becomes emotionally dysregulated, they may react in an emotionally exaggerated manner to environmental and interpersonal challenges by displaying bursts of anger, crying, accusing, passive-aggressive behaviors, or by creating conflict. It is not unusual for a person to have poor reality testing when dysregulated—this relates to sensory pathways being shut down during the period of high emotional reactivity.”

Charles is not the only kid in my life who displays this kind of behavior. Max, a good friend’s grandson who lives nearby in Phoenix, has spent a few hours with me. (Yes, I have play dates from time to time.) I have seen Max decompensate in similar ways, for instance, becoming hysterical after a slight injury or acting out when he loses a game. A few months ago, I spent some time researching approaches to addressing emotional dysregulation. I found this article from the Child Mind Institute. In addition to presenting some therapeutic responses (which, by the way, do not include saying, “Oh, grow up!”), they offer some short videos for teachers’ use.

I decided to introduce Max to Charles, having them both over for a few hours one Saturday to hang out with me. We went on a walk to identify trees with my phone app (see anecdote below), made lunch together, played games (Charles excused himself from this to draw), and take an occasional break to watch one of the videos. I told them that I thought they had something in common, and they were both very willing to share what kinds of thoughts or events led them into strong emotional reactions. It went very well, and I meant to do it again, but didn’t. Maybe when we’re back in Phoenix in the fall?

When I started this post, I was foundering. I was feeling thwarted in my mission to make this a summer of learning for Charles. Until recounting our history together, I had simply forgotten the totality of who he is. I believed that, if I found the magical key, my efforts would help him overcome the obstacles his nature puts in his path. My hope was that writing all this down would lead to clarity, so that I could plan the next session with such elegance that academic progress would be made and emotional calm would ensue. To misquote the Bard, “Oh, what a fool this mortal be!”

OK. Now that I have laid out my history with Charles, I am calmer. The first (off-base) insight that came to me was, “I have to lower my expectations.” But NO, that’s not it. What I need to do is make a brief list of what I’d like to do next time I see Charles, then let go of expectations, take pressure off myself, be humble, present and curious about what will happen. I’m also going to talk to his mother before the session, to hear about what his behavior and reactions are like at home. I fancy myself a miracle-worker sometimes, and although it’s a little disappointing that I’m not, it’s also a huge relief.

While I’m writing, I occasionally preview what the post will look like to readers. It allows me to proofread twice (or more), and being in the role of a reader often suggests better, more honest ways to phrase my thoughts. Last time I previewed, I saw what’s below the title of the blog: Breathe. Find calm. Trust that, strand by strand, over time, the knot will be undone. Hmmm… Good advice.

Postscript

I just hung up from talking to Charles’s mother. As it turns out, I’ve been played. Charles may indeed be somewhat emotionally dysregulated, but over time, he has parlayed that tendency into a manipulation: “Don’t expect too much of me or I will play victim so you’ll feel sorry for me.”

I should have started talking to his mom long ago. She’s on to him, and Charles knows that he will not get far when he acts helpless around her, but she said he still tries it out on others, most recently on his piano teacher and me. So was it worth the many hours I spent worrying about it? I guess not, but given who I am, that’s what I did. I could beat myself up for being a fool, but the energy it took to fret and strategize depleted me. His mother will come in for a few minutes when she drops him off tomorrow so we can reset and agree on a more “no nonsense, no drama” approach. Then she will leave and Charles and I will try again, perhaps with more success.

PPS

I woke up early today thinking about my dad, Ralph. He could be kind of a doofus sometimes, but was always ready to help people in need, whether or not he grasped their situation enough to really be useful. Like him, I sometimes get the wrong end of the stick, earnestly making it my mission to help, but blundering on the way. Ralph would have taken Charles’s outbursts to heart and walked on eggs to be sure to never set him off.

My mother Dorothy, however, would have lowered the boom. She had zero tolerance for “bellering.” [Hmm, I just looked that up and it is not a word. In our house, it certainly was. Maybe it’s a regional (KS) pronunciation of bellowing, but it’s synonymous with belly-aching. Richard’s mom Sallee would have said “kvetching,” but crying as manipulation was more her schtick, not the kids.’]

Dorothy would occasionally use the time-honored “If you don’t stop crying, I’ll give you something to cry about,” but there was a tight-lipped look that was sufficient. This would have been followed by a silent shaming that was far worse than whatever it was we were crying about.

Early in my teaching career, I channeled Dorothy in responding to a sweet kid, Richard Reid, stealing my transistor radio. I was teaching at Williams AFB SE of Phoenix. Richard and I were close, and his dad had suddenly been transferred. In retrospect, his taking my radio was not a malicious act, but a reaction to sudden separation. But lacking that insight, I shot from the hip, responding to him as Dorothy would have with me. I shamed him, then he was gone. It still hurts my heart when I think about it.

I’m glad that years of experience with kids (and years of therapy) have largely taken shaming out of my repertoire, because there’s no way that using it with Charles would have been productive. Ralph’s big-heartedness was in ascendence in me, but too soft an approach is not the answer either. I see Charles in a few hours. I think I’m ready.

from the mouths of kids

It was January when Charles and Max were out identifying trees. They were having a great time, taking turns snapping photos while the other one was writing tree names on a map of our community on a clipboard. I knew it was time to go back inside when they started taking photos of Mac, me, and each other to see what kind of tree they were, but before things got silly, they were being serious about it. At one point, Max walked up to a deciduous tree, bare at that time of year. He said, “That tree is dead.” I told him it was likely going to sprout buds again soon, but he was skeptical. The app identified it as a “Tree of Heaven.” Max looked at me knowingly and said, “I’ll bet ALL dead trees are called Tree of Heaven.”

One evening a few days before we left for Flagstaff, I was walking Mac at night (the only reasonable time to walk a dog in Phoenix in the summer), and I met a neighbor for the first time. She and I chatted for a while, and jigsaw puzzles came up. I told her I wanted to exchange finished puzzles with someone. She was willing to be that someone.

I’m a jigsaw puzzle snob. I search for really special 1,000-piece puzzles and don’t mind spending $20-25 for a good one. I gave her a box of eight or ten high-quality puzzles I had finished. In return, she gave me a box of 500- to 750-piece puzzles she had bought at Goodwill, price tagged $1.49 each. I inwardly shuddered, anticipating the frustration of getting “done,” but finding that pieces were missing. I managed to thank her and stashed the puzzles in a closet.

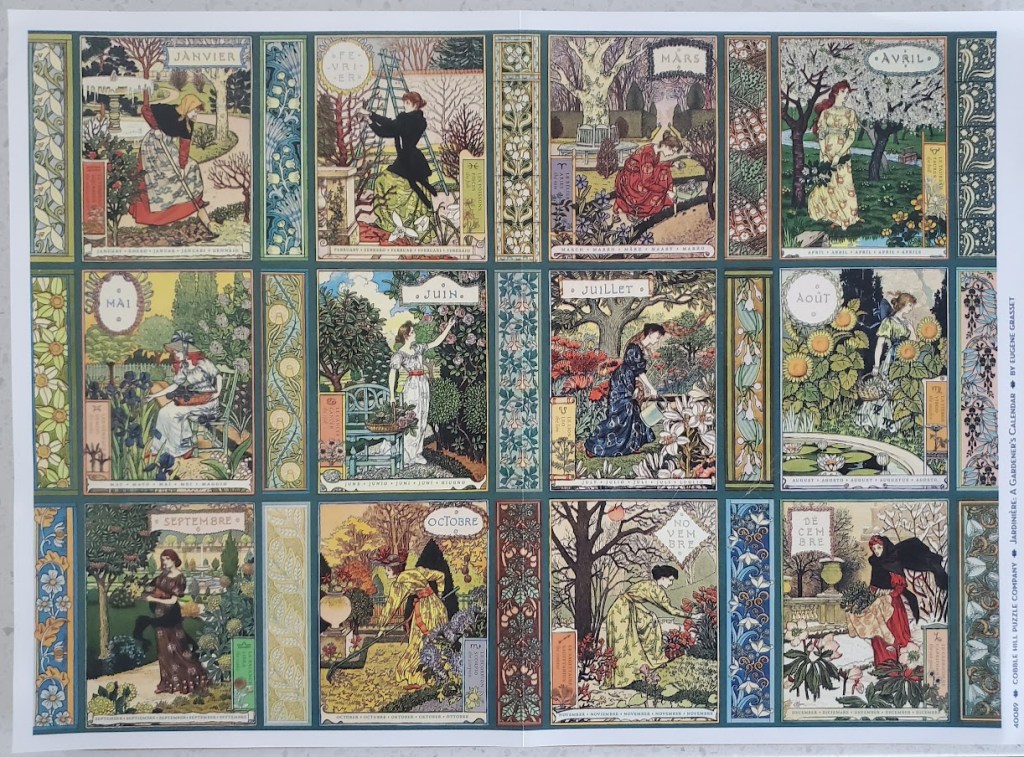

We’re in Phoenix for a few days, so I started the 750-piece one below. It turned out to be one of the most challenging and entertaining ones I’ve done, the more so because all pieces were accounted for. There were five extra ones from some other puzzle! Another lesson in humility, not being such a snob, and letting go of perfection.

One of my own purchases, rich with color and flowered panels that were a joy to match up and put together.

Credit for reflection photo at top: Peter Ralston, photographer, featured in Heather Cox Richardson’s “Letter from an American”

I appreciated your reflections on Charles! I know that kid – from when I was a kid. He grew up fine, as far as I know. His mom was not “on to him” for a lot of years, but we were! (the kid gang that rolled our eyes at him. I felt bad for him, but just couldn’t take it, either). So, there’s that moment when we get caught up in someone else’s strong emotions. It’s interesting to hear how someone else notices, analyzes, and responds. I hope you and Duke are doing well in Flagstaff!

LikeLike

Hi Susan, I love how much time and energy you spend trying to help this one student. Would

that all teachers could be that caring. The heat here is miserable, but I will be getting together

tonight with Kevin and his family. Love to you , Peg

LikeLike

As a school counselor I often worked with/tried to help students who were equally discouraged. So difficult!

LikeLike

Hi Anne and Susan, I was also in education. Taught 4th grade in a suburb of Dallas, and at

a Montessori school. Loved the kids, but didn’t like all the bureaucratic red tape, so switched

to private child care. Hope you’re staying cool and happy, Peg

LikeLike